Appendix 2: basic Linux administration

What's so great about Linux that, back in chapter one, I counted it among my "big tent" technologies? Well let me put it this way: if you're planning to get a workload running on a web server, Internet of Things device, cloud instance, or super computer, then there are overwhelming odds that you'll be working with Linux.Linux is free, stable, (relatively) secure, infinitely customizable, supported by a solid, mature community and, as you'll soon see, available in permutations built to fit all kinds of use cases. And did I mention it's free? Yes. I believe I did.

So since most technology these days is running on Linux platforms, you're going to need at least a basic familiarity with the way its file system, package management, and security controls are designed.

Of course this is only one short chapter and is no substitute for proper administration skills. What's worse, even according to my own teaching philosophy, this chapter is done all wrong. As I wrote in my Linux in Action book,

Linux in Action turns technology training sideways. That is, while other books, courses, and online resources organize their content around categories ("Alright boys and girls, everyone take out your slide rules and charcoal pencils. Today we're going to learn about Linux file systems."), I'm going to use real-world projects to teach.

So, for example, I could have built an entire chapter (or two) on Linux file systems. But instead, you'll learn how to build enterprise file servers, system recovery drives, and scripts to backup archives of critical data - in the process of which, you'll pick up the file system knowledge as a free bonus.

Don't worry, all the core skills and functionality needed through the first years of a career in Linux administration will be covered - and covered well - but only when actually needed for a practical and mission critical project. When you're done, you'll have learned pretty much what you would have from a traditional source, but you will also know how to complete more than a dozen major administration projects. And be comfortable tackling dozens more.I really think that's the better way to teach this stuff. But I also understand that you're probably not looking for complete immersion right now. So here's the shorter version. 440 pages shorter, to be exact.

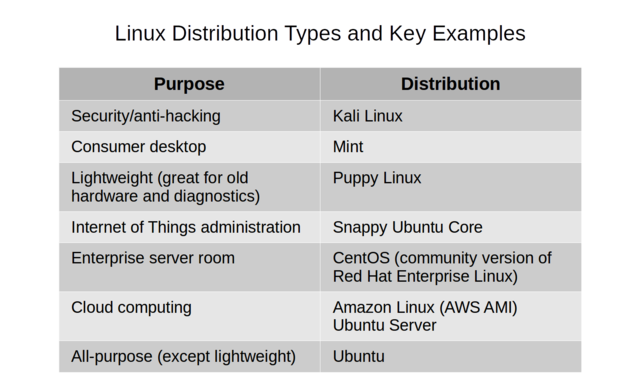

Linux distributions

As I just noted, Linux comes in dozens of flavors called distributions (or "distros"). The idea is that you get to choose the distro that's the closest match to your project needs.Once you start looking, you'll find distros optimized for the cloud, virtual machines, or bare metal servers. There are distros for system recovery, security operations, or cutting edge experimental hardware platforms. There are even consumer distributions for desktops and laptops whose beauty and function will blow you away.

Figure 8.1 should help you choose by showing some of the most popular distributions and their common use-cases.

Common Linux distribution use-cases and popular examples

Consider writing your ISO to a flash drive and trying out the OS as a live USB session. You'll get to confirm that the distro runs on your hardware but your fixed data drive will remain untouched.

Working with root authority

When you first install most Linux distributions, you'll be prompted to create a user account with theoretical administration powers. I say "theoretical" because for normal use, you'll only have authority over your own account resources, but not those of other accounts or belonging to the system itself.But to perform a system administration task that requires editing a system configuration file, you'll need to convince Linux that you've got the authority. To do that, you'll temporarily assume root powers by prefacing you command with

sudo. Thus, to use the nano text editor to open and edit the /etc/group file, you would run this on the command line:$ sudo nano /etc/group

[sudo] password for david:Package managers

One of the greatest pleasures of Linux is the deep and healthy ecosystem of free software that surrounds it. From enterprise-class office suites to professional audio and video editing software to full-featured development tools, there isn't much you can't find among the tens of thousands of available FOSS packages.But what's even better is the fact that all that software is managed by integrated package managers. What's a package manager? It's a local front end that connects your computer to remote software repositories.

But it's much more than that. The mainstream package managers (in particular APT for Debian/Ubuntu/Mint systems and YUM/DNF for RHEL/CentOS/Fedora) will also...

- Actively curate the online repos to remove buggy, outdated, or dangerous packages.

- Install and remove software on request, invisibly ensuring that all dependencies are working.

- Manage the software you've already installed, automatically updating it when necessary.

- Miraculously recover your system state after failed or interrupted managements sessions. I say "miraculously" because there's no other word I can find that accurately describes it.

sudo.$ sudo apt update[installed] note tells us the current status of the package$ apt search git

git/xenial-updates,xenial-security,

now 1:2.7.4-0ubuntu1.3 amd64 [installed]

fast, scalable, distributed revision control system$ sudo apt install gitSSH: secure remote connectivity

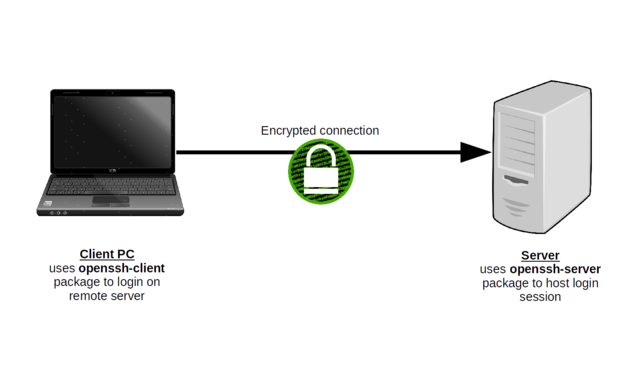

From the looks of you, I'd say you do most of your work on a laptop. But I'd also say that the odds are you're not planning to use your laptop as your web sever. So then how will you configure your server or move your precious applications over? Network connectivity, right?Sounds great. But are you aware that any data transferred across a public network can be intercepted, read, and modified? The whole thing, passwords and all. Unless, of course, the data is properly encrypted.

The single best way to safely create and encrypt remote connections is using Secure Shell (SSH). The protocol is so good - and so popular - that it's now available not only where you'd expect to see it on Linux and macOS, but even natively on Windows 10.

Here's how it works. We usually refer to your laptop as the SSH client, and the server, since it will host your sessions, as the SSH server. Make sure that the package

openssh-server is installed on your server and either openssh-server or openssh-client on your laptop.$ sudo apt update

$ sudo apt install openssh-serverssh, the username whose account you'll use on the server (my example is "ubuntu"), and the server's IP address or domain name.ssh ubuntu@10.0.3.141

ubuntu@10.0.3.141's password:

Welcome to Ubuntu 16.04.1 LTS (GNU/Linux 4.4.0-109-generic x86_64)

* Documentation: https://help.ubuntu.com

* Management: https://landscape.canonical.com

* Support: https://ubuntu.com/advantage

Last login: Thu Dec 7 19:01:45 2017 from 10.0.3.1

ubuntu@server:~$

Logging in to a remote server through an encrypted SSH connection

Secure file transfer

Now what about that application code sitting on your laptop? OpenSSH has another tool for you: Secure Copy (SCP). Let's say that you've got a Java JAR archive you want to transfer over. Easy. Here's what you'd do from your laptop:$ scp /home/myusername/code/myapp.jar \

ubuntu@10.0.3.141:/home/ubuntu/How about copying files in the other direction? Suppose you're on your laptop and you want some log files moved from the server to your laptop. Well, assuming the logs are currently in the "ubuntu" user's home directory on the server, here's how that would work:

$ scp ubuntu@10.0.3.141:/home/ubuntu/logfiles.zip .The Linux file system

Great start. SSH is your way into your Linux server, software is handled via APT or YUM, and you impose your imperial will by invoking sudo. All that's left is learning how to actually do administration stuff Linux.Remember this single piece of wisdom and you'll never go far wrong:

Everything in Linux is a plain text file.The trick is simply finding the right files and figuring out what to do with them. So let me introduce you to the Unix/Linux Filesystem Hierarchy Standard.

The Unix Filesystem Hierarchy Standard

With relatively few exceptions, all Linux distros will organize files the same way. To a large degree, you'll find a similar layout on the Unix-based macOS operating system some of you might have heard about. Here's how things look when you list the contents of a typical Linux root directory:$ cd /

$ ls

bin initrd.img mnt sbin usr

boot initrd.img.old opt snap var

dev lib proc srv vmlinuz

etc lib64 root sys vmlinuz.old

home media run tmp- The /etc/ directory contains configuration files that define the way individual programs and services function.

- /var/ is where Linux keeps variable files belonging to the system or individual applications. These are files whose content changes frequently through the course of normal system activities.

- Individual users are given directories for their private files beneath the /home/ directory.

- /lib/ contains shared software libraries.

- The binaries for most command line tools live in /bin/.

Getting around

I'm sure you won't have any trouble with this stuff. When you log into Linux - or open a new terminal shell within a GUI session - you'll normally find yourself in your user's home directory. Assuming your user is namedubuntu, this is what running pwd ("present work directory") will look like:$ pwd

/home/ubuntuls:$ mkdir newdir

$ ls

newdircd ("change directory"):$ cd newdirtouch will create a new, empty file, and cp will copy it to a new location - or just make a copy of the original with a new name if you don't specify a different location.$ touch newfile

$ cp newfile newerfile

$ ls

newerfile newfile$ rm newerfileCTRL+x to exit, and y to save the file.$ nano newfile/). /var/log/, by the way, is where most system logs are kept. Feel free to take a look around.$ cd /var/logObject permissions

By design, Linux is a multi-user system. That means a single Linux computer can be accessed and used by an infinite number of users and processes concurrently. This is one of the many features that makes Linux so incredibly useful: it allows a level of flexibility and collaboration that has no equal in IT.But it also means that there's a greater need to protect resources from unauthorized access. You don't want one team of developers to accidentally messing with the config files belonging to another team. And, of course, no one wants the guys in marketing messing with anything.

So all the objects in a Linux file system will have a set of attributes precisely defining who gets to do what. Those attributes - known as permissions - are broken down into three categories: read (

r), write (w), and execute (x). And users are divided into three classes: the object's owner (u), the object's group (g), and all others (o).ls -l will display an object's attributes. In this example, the first -rw tells us that the owner has read and write (i.e., edit) permissions, the group also has read and write permissions, and all others can read, but not write the file.$ ls -l

-rw-rw-r-- 1 ubuntu ubuntu 0 Jan 14 00:33 newfilechmod. This example will add (+) write permissions to others (o).$ chmod o+w

$ ls -l

-rw-rw-rw- 1 ubuntu ubuntu 0 Jan 14 00:33 newfilechown to change an object's ownership. Right now, as you can see, the file is owned by the ubuntu user and belongs to the ubuntu group. This command will transfer ownership to a user account named steve, while leaving the object in the ubuntu group.$ sudo chown steve:ubuntu newfile

$ ls -l

-rw-rw-rw- 1 steve ubuntu 0 Jan 14 00:33 newfileHelp

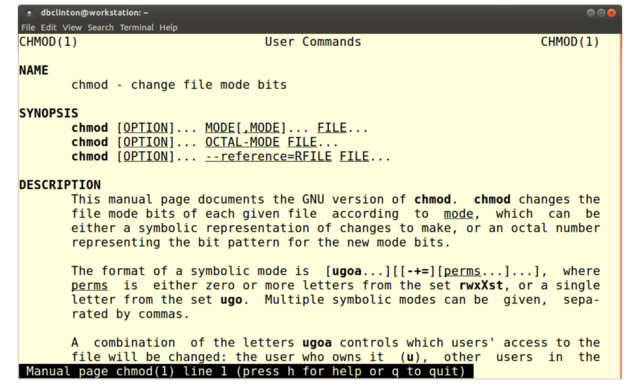

One last thing. When you run into trouble, your first stop will probably be the internet...and for good reason. But don't ignore the wealth of helpful information available to you on the Linux command line through theman system. Typing man followed by name of the command you're stuck on will open a well arranged guide to the command's use.$ man chmodchmod.

The first screen from the man file for chmod